As part of a month long build up to International Women’s Day Celebrations on the 8th of March, the YCL will be publishing daily articles highlighting the exemplary role played by women in the international communist & working class movement.

As part of a month long build up to International Women’s Day Celebrations on the 8th of March, the YCL will be publishing daily articles highlighting the exemplary role played by women in the international communist & working class movement.

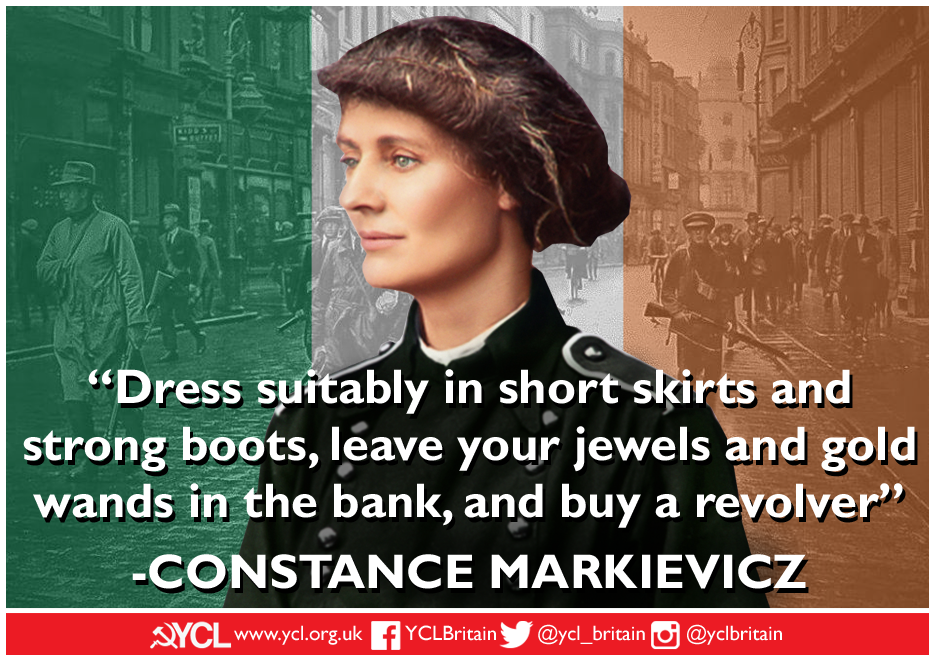

Today we discuss the life of the ‘Rebel Countess’ Constance Markievicz, figurehead of the anti-colonial struggle in Ireland.

YCLers are encouraged to host, support and participate in celebrations locally to bring the message of International Women’s Day into Our workplaces, colleges and schools, and communities.

Constance Georgine Markievicz (Gore-Booth) (1868 – 1927) was born in London on 4th February 1868, to Sir Henry Gore-Booth, an Arctic explorer and Anglo Irish landlord, and his wife Lady Georgine Gore-Booth. During the Irish famine of 1879-80, Sir Henry provided free food to the tenants on his estate and refused to accept any rent payments. This example from her father is what inspired a deep concern for the working class and the poor, in Constance and her younger sister Eva. A childhood friend, W.B. Yeats , frequently visited the family home and inspired the sisters with his artistic and political ideas. Constance’s sister Eva later became involved in the women’s suffrage and the Labour movement, however Constance initially did not share her sister’s ideals.

In 1882, deciding to train as a painter, she went to study at the Slade School of Art in London where she lived at the Alexandra House for Art Pupils. It was during her time here that she became politically active, joining the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS). She later moved to Paris to study at the prestigious Académie Julian, where she met her future husband Casimir Markievicz, an artist from a wealthy Polish family from Ukraine. Constance and Casimir were married in London on 29th September 1900, welcoming their daughter Maeve in November 1901. She also undertook the role of a mother to Casimir’s son Stanislas, from his first marriage.

The Markieviczes settled in Dublin in 1903, with Constance gaining a reputation as a landscape painter. In 1905 she was instrumental in founding the United Arts Club, along with artists Sarah Purser, Nathaniel Hone, Walter Osborne and John Butler Yeats. Sarah Purser, hosted a regular gathering in her home where artists, writers and intellectuals on both sides of the nationalist divide gathered. It was here that Markievicz met revolutionary patriots Maud Gonne, Michael Davitt and John O’Leary. In 1907 she rented a cottage in the Dublin countryside, where the previous tenant had left behind copies of “The Peasant and Sinn Féin”. These publications are what propelled Markievicz into action.

Markievicz became actively involved in repbulican politics in Ireland, joining Sinn Féin and Inghinidhe na hÉireann (‘Daughters of Ireland’), a revolutionary women’s movement founded by actress and activist Maud Gonne. In the same year, Markievicz played a dramatic role in the women’s suffrage campaigners’ tactic of opposing Winston Churchill’s election to Parliament during the Manchester North West by-election, flamboyantly appearing in the constituency driving an old-fashioned carriage drawn by four white horses to promote the suffragist cause. A male heckler asked her if she could cook a dinner, to which she responded, “Yes. Can you drive a coach and four?” Her sister Eva and fellow suffragette Esther Roper, who Eva had moved in with, both campaigned against Churchill with her. This in part, as a result of the dedicated opposition from the suffragists, caused Churchill to lose the election .

In 1909, along with Bulmer Hobson, Markievicz founded Fianna Éireann, a para military republican organisation that taught boys how to use firearm. However at the first meeting held, she was almost expelled on the basis that women didn’t belong in a physical force movement, but Hobson supported her and she was ultimately elected to the committee. She was jailed for the first time in 1911 when she spoke at an Irish Republican Brotherhood demonstration, attended by over 30,000 people, organised to protest against George V’s visit to Ireland. She participated in throwing stones at photos of the King and Queen and burning a British flag taken from Leinster House, which ended up with James McArdle being imprisoned for a month because of the incident, despite Markievicz testifying in court that she was responsible for it.

Markievicz joined James Connolly’s Irish Citizen Army in 1913, to defend the demonstrating workers from the police force. She recruited volunteers to peel potatoes in a basement, while she worked with others distributing the food. As all of the food was paid using her own money, this resulted in her selling all of her jewellery and taking out many loans. In the same year, she ran a food kitchen to feed poor school children, with the help of Inghinidhe na hÉireann.

Fashion advice attributed to Markievicz was: “Dress suitably in short skirts and strong boots, leave your jewels and gold wands in the bank, and buy a revolver”

As a member of the ICA, Markievicz took part in the 1916 Easter Rising. She designed the Citizen Army uniform and composed its anthem, based on the tune of a Polish song. In the Rising, she fought in St Stephens Green, where according to one account, she shot and killed a member of the Dublin Metropolitan Police. Geraldine Fitzpatrick, a district nurse recorded in her diary what she saw when returning to the nurses home after duty:

“A lady in a green uniform, the same as the men were wearing (breeches, slouch hat with green feathers etc.) the feathers were the only feminine feature in her appearance, holding a revolver in one hand and a cigarette in the other, was standing on the footpath giving orders to the men. We recognised her as the Countess de Markievicz – such a specimen of womanhood. There were other women, similarly attired, inside the Park, walking about and bringing drinks of water to the men. We had only been looking out a few minutes when we saw a policeman walking down the path from Harcourt Street. He had only gone a short way when we heard a shot and then saw him fall forward on his face. The Countess ran triumphantly into the Green saying “I got him” and some of the rebels shook her by the hand and seemed to congratulate her.”

The Stephens Green post held out for six days, only ending the engagement when a copy of Pearse’s surrender order was brought to them by the British. They were all taken to Dublin Castle, with Markievicz being sent to Kilmainham Gaol, being cheered on by crowds as they walked through the streets of Dubling. Markievicz was the only female prisoner out of 70 to be put into solitary confinement. At her court martial on 4 May 1916, Markievicz pleaded not guilty to “taking part in an armed rebellion…for the purpose of assisting the enemy” but pleaded guilty to having attempted “to cause disaffection among the civil population of His Majesty”. She told the court “I went out to fight for Ireland’s freedom and it does not matter what happens to me. I did what I thought was right and I stand by it.” Originally sentenced to death, this was commuted to a life sentence, based solely on the account of her gender. When she was told of this, her response to her captors was “I do wish you lot had the decency to shoot me”

In 1917, along with other members of the Rising, she was released from prison after being granted general amnesty from the government. At the 1918 general election, she was elected for the constituency of Dublin St Patricks, taking 66% of the vote, making her the first woman to be elected to the House of Commons. However in line with Sinn Féin, she did not take her seat. From April 1919 to January 1922 Markievicz served as Minister of Labour in the second and third ministry of the Dáil. Holding cabinet rank from April to August 1919, she became both the first Irish female Cabinet Minister and at the same time, only the second female government minister in Europe.

Markievicz left government in January 1922, but was elected in the 1923 general election for the Dublin South constituency, again not taking up her seat. However, her republican views would lead to her to being sent to jail again. In prison, she and 92 other female prisoners went on hunger strike. Within a month, she was released.

In June 1927, she was re-elected to the 5th Dáil, but sadly passed away 5 weeks later before she could take her seat. Markievicz passed away on 15th July 1927 due to complications with appendicitis. She had given away her wealth and died in a public ward “among the poor where she wanted to be.”