Boxing Day was the 120th anniversary of Mao Zedong’s birth. Ben Chacko assessed his legacy today. This article first appeared as a feature in the Morning Star 24/12/2013.

This month in Shenzhen a 50-kilo gold, jade and precious gem-studded statue of Mao Zedong was unveiled to celebrate the Chinese revolutionary’s 120th birthday, which fell on December 26.

The tribute was rather ironic. Would the ferociously egalitarian Mao appreciate his likeness being cast in such material? Is Shenzhen – the first special economic zone in China, bordering the former British enclave of Hong Kong and the site where the Chinese Communist Party’s controversial flirtation with market economics began – an appropriate place to honour a man who waged the bloody cultural revolution against alleged “capitalist roaders”?

Yet honour him it did, despite assessments like those of my one-time university lecturer Dr Rana Mitter, who famously imagined the ghosts of Mao and his Nationalist Party adversary Chiang Kai-shek wandering around modern China – Mao lamenting while Chiang crows in triumph.

Mao’s reputation has perhaps suffered the greatest reversal of fortune of any of the 20th century’s communist leaders in the West.

His cult of personality reached fever-pitch in the cultural revolution in his native land – it was “possible to count the stars in the highest heavens, but impossible to count his contributions to mankind” – but it also spread to Europe and the United States, where students and hippies who would have shunned any association with Soviet socialism chanted “Mao for world president” and brandished little red books.

Now he is seen very differently as a pitiless tyrant who supposedly crushed his opponents underfoot and unleashed unprecedented economic disaster on his country.

It’s fair to say that the entirely negative judgement of Mao epitomised by Jung Chang’s much-feted demonography of the Chinese leader is just as much an exaggeration as the praise once heaped on him by legions of red guards.

As the Shenzhen statue shows the Chinese have a rather more nuanced attitude to someone still known simply as “the chairman.”

Millions queue to view his embalmed body in Tiananmen Square, but slavish adoration is definitely out. The Communist Party says he was broadly right until about 1956 but thereafter “mixed at best and frequently quite wrong.”

Millions queue to view his embalmed body in Tiananmen Square, but slavish adoration is definitely out. The Communist Party says he was broadly right until about 1956 but thereafter “mixed at best and frequently quite wrong.”

The view was clearly shared by Chen Yun, architect of the 1980s economic reforms, who remarked that if only Mao had died in 1956 he could be remembered as a great revolutionary hero, but as he died in 1976 “there is nothing we can do about it.”

Mao’s two main campaigns after that date were disasters on such a scale that Chen’s grim assessment is perfectly understandable.

The Great Leap Forward was an attempted leapfrog into communism – bypassing socialism – which wrecked industry and caused a terrible famine.

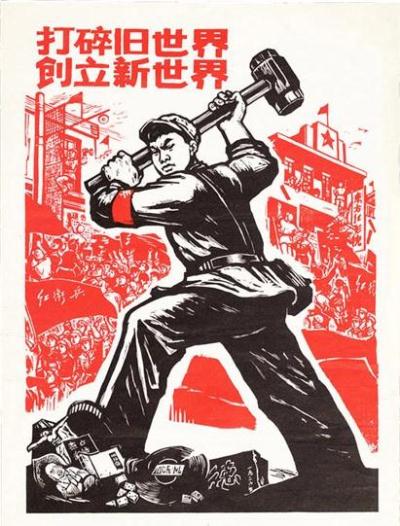

The cultural revolution unleashed widespread and random brutality, destroyed thousands of cultural treasures and shut down the education system for a decade.

Less widely known is the impact on the environment. A crude definition of all animals not obviously useful to people as “pests” resulted in the near-extermination of the Chinese alligator and the South China tiger, which until the 1950s was the commonest tiger in the world. Since the 1980s the Chinese government has desperately backtracked, running schemes which hope to save both species, but they remain critically endangered.

Communists will have other accusations to throw at the “great helmsman.” Though the Communist Party’s 1935 Zunyi conference, held during the Long March, was right to conclude that a Chinese revolution would be powered by the peasantry rather than the tiny urban working class, a peasant-first fixation on Mao’s part did hold back economic development. China was the only country on Earth where the proportion of the population living in cities actually declined between the 1950s and the 1970s.

Even more significantly, he was an inconsistent internationalist.

China did reach out to the developing world from the 1950s, providing economic assistance to Africa in particular, and its effort during the Korean war – in which Mao’s own son died on the front line – was decisive in preventing a US victory.

But the breach with the Soviets was a serious blow to socialism and its behaviour afterwards – treating anyone anti-Soviet as an ally, including butchers like General Pinochet and Pol Pot – a stain on the country’s reputation.

The charge-sheet is pretty damning. Why, then, won’t China let go?

Why is Mao Zedong Thought still enshrined alongside Marxism-Leninism as the party’s guiding ideology? Why do doctors and nurses proudly wear Mao badges to indicate their opposition to private health care? Why is Mao seen as such a universal symbol of good luck that his image is dangled from the rear-view mirrors of cars to prevent traffic accidents?

The truth is that Mao’s legacy is just as littered with positives.

We can scotch a few myths to begin with. The Mao years were not a national catastrophe.

Economic growth, as Eric Hobsbawm noted, was far more impressive than in most of the developing world, including neighbouring India. The country was unified following a lengthy and crippling civil war and a genocidal invasion by imperial Japan.

Mao’s own contribution to these victories was significant. His guerilla warfare tactics later influenced the Vietnamese struggle against imperialism, and his book On Protracted War is still studied by military officers worldwide – including in Britain.

Diseases including leprosy and bubonic plague were eradicated and life expectancy soared from 35 to 65 under Mao’s leadership. A largely illiterate country was taught to read and write.

And the Chinese Communist Party, to its credit, never submitted to a personal dictatorship. Mao didn’t execute his political opponents – in fact most of the 1980s party leadership was made up of them.

Frequently the central committee rejected Mao’s policies and critics argued with him till the end – Deng Xiaoping, for example, was purged more than once and denounced in national campaigns, but was always back at the top table before long. He even baited Mao by ostentatiously turning his deaf ear to him whenever the chairman spoke at meetings.

Allowing political figures this leeway is a valuable tradition the Chinese party has maintained – former leaders, whether deposed like Hua Guofeng or retired like Jiang Zemin, have retained central committee membership and continued to contribute to national policy-making.

Allowing political figures this leeway is a valuable tradition the Chinese party has maintained – former leaders, whether deposed like Hua Guofeng or retired like Jiang Zemin, have retained central committee membership and continued to contribute to national policy-making.

But the ultimate reason not to write Mao off is to take a look at the achievements of the Chinese revolution.

On the 60th anniversary of the People’s Republic’s foundation I remember watching people interviewed on Chinese television.

A former US soldier, deployed to the country during the 1940s, remembered the misery, the starvation and the desolation he had seen, coupled with the injustice of the part-colonial, part-feudal system that dominated China then and contrasted it with the economic powerhouse that the country is today.

A former Tibetan slave recalled the day the monasteries’ landholdings were broken up and he was told he was free.

But perhaps the most moving interviewee was an old woman who had joined the Communist Party during the Long March. Born illegitimate, she had never had equal status with the other people in her village. In fact she hadn’t even had a name and was simply addressed as “girl.”

“I remember when the Red Army came,” she said. “They gave me my first pair of shoes. And they gave me a name.”

It is this story of human dignity that defines the power of the Chinese revolution. As Mao declared from the gates of the Forbidden City – to enter which meant death for commoners in the days of the empire – “The Chinese people have stood up.” Not merely by rejecting foreign control but by throwing off the shackles of the old society.

And as the long-suffering Deng Xiaoping said of the man who purged him twice, “without Mao there would be no new China.”

That’s why, despite all his many and serious faults, we shouldn’t be ashamed to raise a glass to the chairman on his birthday.